The storm blew me past the busy port of Guaymas, where I’d intended to anchor and check out boatyards, and then San Carlos, several miles north. Next thing I knew I was passing an island in the dark, in high chop and higher winds—30 knots with stronger gusts. The navigational system shows tankers in the area, but I can’t see them, though they are 500-600 feet long. Can they see me? I crawl forward and lash four lanterns on deck, then obsessively check AIS for updates on their whereabouts.

Lightning. Not something you want to see while under a forty-foot mast. Thunder. More lightning, all around me. Then rain. Hard. Bouncing. A deluge.

But my first reaction upon realizing the storm was going to hit? Glee. Glee?! I’ve been terrified of getting caught in a storm on Habibi, and here it is—reality. No more dread, simply deal with it. The rain washed us clean, and I began singing. Hours later, it was over, and dawn broke. We had survived.

The next night, another storm. No glee this time. I was tired. I wanted to be there already, and There had just disappeared in our wake. Another long night. When dawn broke this time the wind didn’t let up. Still with the 30 knots. Now with a 5-6’ swell that wanted to bash us in the beam. I could aim for nearby beach anchorages, but that’s where the waves were breaking. Not really up to surfing Habibi.

Instead I target Isla Esteban, and arrive at sunset. Oh, did I mention the depth-sounder had been wacky for the past few days? I couldn’t trust it. Or shouldn’t I trust the chart? Are we at 1000 feet or 5? Well, we aren’t running aground…

I hear seals, and this cheers me. I head for a marked anchorage, but the current is against me so I turn around. Across the channel there’s supposed to be another boater-used spot, but the wind is pushing us west, I’m unsure of the depth, so let the current take us around to yet another anchorage. Okay. Is it really 189 feet? It supposed to be 17!

I drop the anchor. The depth-sounder is right and I don’t have enough rode (150 feet of chain, then 100 feet of nylon line) to dig in, so it’s dangling. I’m unable to haul it by hand, muscles exhausted after days in stormy seas. The electric windlass won’t haul the nylon line. So I run it back to a manual winch on the mast. Jumping up to push down and crank it, I haul the rode until it switches to chain and I can catch it on the windlass and let the motor do the work. It takes about an hour.

The engine is off, so we’re quietly drifting. I pull the jib sheets (two lines running from the cockpit to the foresail at the bow), and unfurl it again. Crawl below and crash on a settee in the salon for a minute. Habibi sails halfway up Shark Island while I sleep.

Daylight of the third day, I motorsail to yet another charted anchorage, and this one takes. Agua Dulce. Zero humans or habitations. Valhalla. 77 hours since I left Topolobampo.

More lightning plays along the eastern horizon in the evenings, and strong winds, but the anchor holds. Bright constellations overhead. Then a swarm of flies. Swaddled in netting. Sweating.

After six days and nights (lightning redux), I’m rested enough to continue northwest toward the next boatyard. Wind and swell follow me and don’t let up. Ever. Sometimes only 14 knots, but usually more than 20. Motor switch is now wonky. Batteries refuse to charge. Is the drinking water mildewy? Habibi reflects my state of bruised body and mind. Once I found myself at the helm, fighting with the autopilot, unsure if it was on or off, or what direction we were heading. Delusional. Elvis sings, “Caught in a trap. Can’t walk out.” Remember the rest: “Because I love you so much, baby.” There is always a solution. Breathe.

It wasn’t all terrifying. There was a day that reminded me of an occasional childhood peace I felt in Santa Monica. Habibi sails at a steady five knots, not intense, not heeling. The sky is blue with high cirrus clouds. It is temperate. The swell is only a foot or so, no sudden pitches. Contentment stole across me as I sat under the bimini, watching the ocean, the heavens, the tawny land in the distance. All is well. All is good. The journey is long and arduous, but there are moments of tranquility.

Puerto Peñasco is a shallow harbor, and it’s after midnight again. Can’t see a marina or any free space to dock, only many big metal boats cheek by jowl. Turn around and almost hit a shrimper coming into port. But I try again, because the wind and waves are high in the outside bay. Then, nope, can’t risk it. Simply cannot make out what things are in the dark. Tiredly head out, just missing a jetty. Anchor a mile outside, the swell trying to throw me overboard, and the badly furled jib coming loose and percussively beating itself to death.

Earplugs in. Meditate. Await the dawn. Then sponge bathe. Put on the hot pink Capitana shirt to remind me who I am, and clean shorts. Wiggle the motor switch until it catches. Creep forward to raise the anchor. Bam. Bam. Bam! The swell lifts Habibi’s bow and drops her, again and again. Understand the great value of crew. But it’s me, and only me right now, right here.

In the daylight, I can now see the fleet of ships I did not hit, the shoal I did not run aground, the rocks I missed the night before. The electronic chart was wrong again, this time about the shape of the channel. So many ways to come to grief. Yet I didn’t. More than 400 miles from Topolobampo, above latitude 31, I pass the Navy pier, spy a space five meters farther, and angle into it. Put Habibi into reverse to avoid hitting the L-shaped dock, so of course she shifts her butt to starboard. Jump off the stern as it bumps the dock and tie a line to a rusty cleat. We are fast. At last. Just the aft.

See a man with a dog and call to him for help. After resourcefully tying Habibi’s bow, including the use of a ¨Mexican escalera¨ (a plank), Manuel phones the boss about the only empty slip in the marina. Another dock worker assists the move around the three-story party boat, appropriately named Fiesta, pushing me off a fishing charter neighbor. Habibi is almost 12 feet wide. There’s just enough room in the slip, a foot on either side.

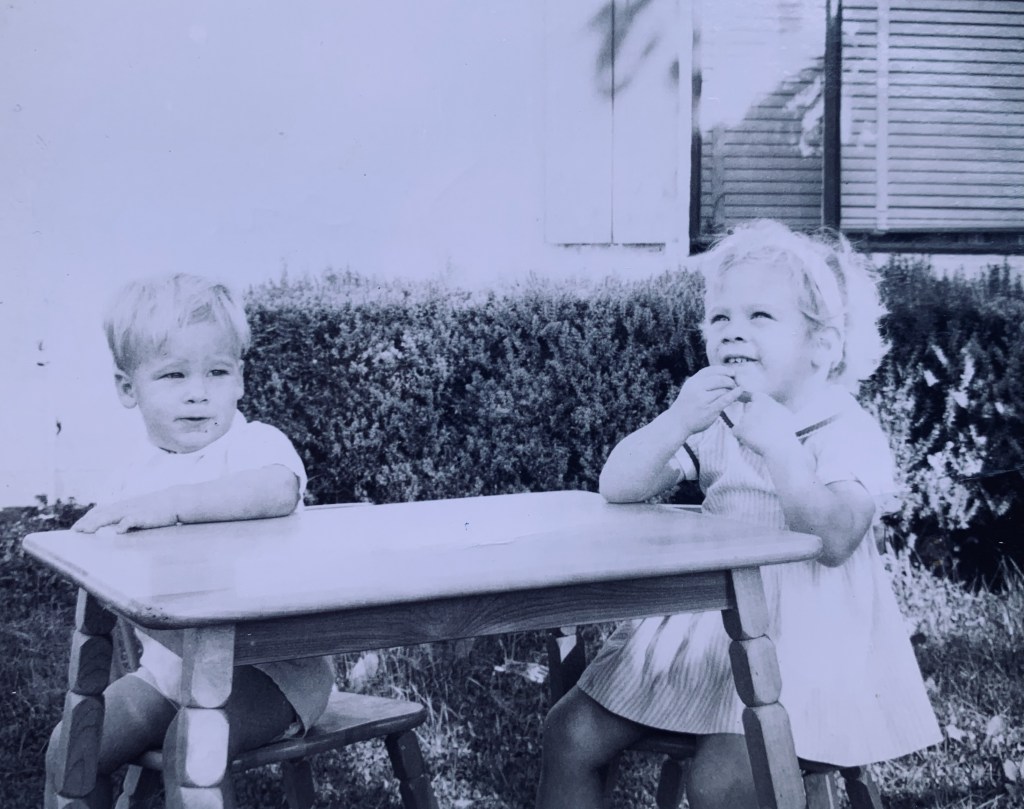

We are done by nine o’clock in the morning. Plugged into electricity, hose attached to a spigot. 200 miles from my birthplace outside of Phoenix AZ. An aunt once told me that we visited the Gulf of California, probably near here, when I was…. two? three? Maybe my first saline water. Life is a nautilus shell, around and around and around.

After a short nap, I pay for a month in Sun Marina, then check in with the Capitanía, the government arm of the harbor. Paperwork complete, I find myself turned around in foreign territory. Not the first time. A vertical sign down a side road proclaims ‘Sapporo.’ Inside next to the air conditioner, I order a shot of sake and enough food for a family of four. Sated and tipsy, find the marina, carrying leftover udon soup and Mex-Thai salad. Bathe with soap in the bathhouse. Conk out for 12 solid hours. Without bracing my body against the teak lockers under the cabin couches. Because I am only horizontal, not rolling or shaking or bucking with the flow of the ocean.

“Life can be different,” writes Robin Sloan in Moonbound. “It does not all need to be cruel effort.” Perhaps, soon, I can stop putting myself in dangerous situations. Over-adrenalization is a familiar occurrence. So much melodrama in the family template! I want this pattern interrupted.

I thought I was going to die. Capsize. Lightning strike. Crash into rocks. Drift into a pinnacle. Sink.

I thought I was going to die, and so I made peace with it. I have loved. I have been loved. The rest is lagniappe, a gift.

Leave a comment